Musings by JY

Technology in Sports: How Automated Pitch Tracking Works in Baseball

Often in the aftermath of verdicts for huge showdowns in professional boxing (Fury v. Wilder 1, Canelo v. GGG 1, and more recently, Lopez v. Lomachenko), the world’s attention turns to the ancient question of how boxing matches are scored and why the sport continues to have so much difficulty coming to a consensus on the results of a match. This is not surprising, since the sport relies on subjective judging (on effective aggression, ring generalship, and defense) rather than on an authoritative scoring technology. With the exception of the Nevada Athletic Commission, the sport is not even aided with the help of instant replay. CompuBox is as close as we come to obtaining any form of statistics on a fighter. But even that, is just two operators at ringside manually pressing buttons for “jab connect”, “jab miss”, “power punch connect”, and “power punch miss”. In other words, in the world of professional boxing, judging relies on nothing but one’s eyes, which can be so incredibly deceptive and so easily influenced by one’s knowledge and preferred style of fighting.

This is, however, a choice. I think it makes the fights more entertaining for the viewers as it gives a sense of active participation, and creates, intentionally or not, narratives of robberies and revenge. I think it’s unfortunate for the fighters who end up with the short end of the stick, but these are professionals who understood the risks and consequences when they sign the contracts.

So why am I here? Well, as a result of thinking about Compubox and how imaging techniques can aid stats collection, I got very curious: how do other sports do it?

Pitch Tracking in Baseball

We will use TrackMan as the basis for everything described below. If you’ve never heard of TrackMan, it was a component within Statcast. As a caveat, I’m not well-versed in the subject (nor in the physics behind it), so the information below is merely what I understand from research, not to be taken as the ground truth.

Doppler Effect

TrackMan is a 3D Doppler radar system, and thus relies on the Doppler effect to determine the speed and radial direction of its target objects (in this case, the baseball). The Doppler effect is the change in frequency of a wave as the source of the wave and an observer move toward or away from each other. A common example here is a car honking as it zooms past you; you, the observer, will typically hear the honk drop in pitch as the car speeds away. This is because the frequency of the honk emitted by the car increases as the car moves closer towards you, and the frequency drops as the car moves away. Given that frequency of sound is pitch, the Doppler effect presents itself as a tonal drop in the example.

This change in frequency is the basis for our insights into the moving object’s velocity. As a simplification, you can imagine that the systems works by doing the following:

- The system emits a signal at a wavelength of $\lambda$ and at a given frequency $f_{transmitter}$, which is reflected off the baseball as the ball travels towards home plate.

- The reflected signal is received by the system with a frequency of $f_{received}$.

- The change in frequency, or the doppler shift, is then used to calculate the velocity of the object, where $f_d = f_{received} - f_{transmitter} = \frac {2V_r} \lambda$, where $V_r = Vcos(\theta)$. Hence we can solve for V as the velocity of the pitch.

- For the mathematically inclined, you can derive the equation by differentiating the total phase change with respect to time and solving for radial velocity.

Phased Array

In order to replay the trajectory of a pitch and moreover call the pitch, the system must continuously record the positioning of the ball as it travels from the pitcher’s mound towards home plate. To fully map out of the trajectory, the system needs to be able to detect the following information:

- $r(t)$: the distance of the ball from the TrackMan system at a given point in time t.

- $\theta(t), \phi(t)$: in a 3D plane, in addition to distance, we need two orientation angles to determine an object’s exact coordinates in the plane at a given point in time t. This is again with respect to the TrackMan system’s location.

To get $r(t)$, we simply calculate based on the velocity of the ball and the starting position, which is just the distance from the TrackMan system to the pitcher’s mound. So this is easily accomplished.

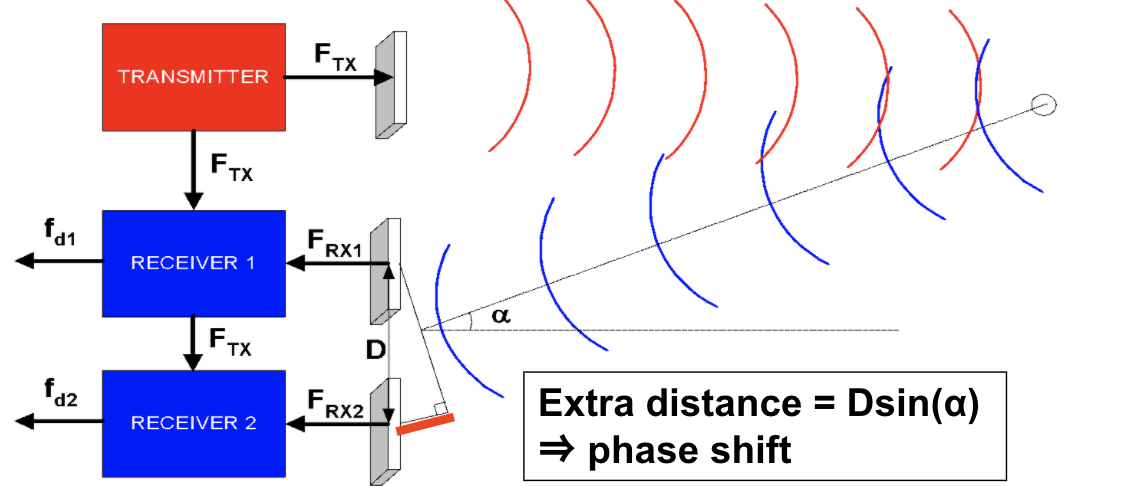

To obtain the orientation angles however, we need to rely on phase shifts. To get a mental model of how this works, look at the image below:

In essense, if a signal is arriving at an angle, by placing multiple receivers a distance $D$ apart, we can calculate the angle from the resulting phase shift and $D$. In this case, since we require two angles, the system must be equipped with at least three receivers. Unfortunately there’s not a lot of public information available on the exact configuration of the TrackMan system, so I’m just speculating from logic here.

From $r(t), \theta(t), \phi(t)$, we can then convert to exact field coordinates using the location and orientation of the TrackMan system, which is typically mounted overhead above and slightly behind home plate. If we do this for $t$ in range from when a pitch was released to when the pitch arrived at home plate, we can effectively graph the trajectory of the ball for each pitch. With optical detection in place to automatically set up the dimensions of a strike zone, we now have the semblance of what a barebone Statcast looks like on TV.

How Well Does This Work?

In scientific analysis, there are two types of errors: systematic error and random error. A systematic error is one where the device is inaccurate due to a bug or a calibration bias, meaning that the error can and should be fixed. Random errors on the other hand, are intrinsic to the measurement process. Random errors can be minimized but never completely eliminated. In the case of something like TrackMan, the systematic errors can be improved upon through better calibration and data analysis over the course of a season. However, such a system, due to its reliance on the Doppler effect, will always be susceptible to random errors, for example, due to the occasional radio frequency interference.

In the specific case of baseball, while the sides of the strike zone is clearly deliminated by the width of the home plate, the definition for the vertical part of the zone leaves a lot of room for interpretation. So even if TrackMan were to have 100% accuracy, it still would not be able to replace an umpire until we come up with a precise, uniform definition of the strike zone.

In conclusion? Everyone loves fun visuals, and TrackMan works well if you don’t take it too seriously, and the data it collects should serve as an incredible tool for teams. The technology is more sophisticated than two poor souls pressing buttons to track punches, but it’s still not good enough to authoritatively call pitches and replace an umpire, despite recent proposals and testing of a RoboUmp concept. After all, if we are going to take the human element out of the game and (more importantly imho) take away the entertainment of managers getting in the faces of umpires, we better be perfect with every call.

It’s worth noting that for 2020, Statcast replaced TrackMan with Hawk-Eye. This is a significant shift since Hawk-Eye uses optical tracking rather than radar technology. So we are still trying to improve the technology, and perhaps some day RoboUmp will be a reality. I don’t know much about Hawk-Eye, but will report back if I get a chance to take a deeper look.

That’s all for today. Next time – maybe a survey of some cool gadgets in F1.

Written on December 19th, 2020 by JY